- Home

- Anthony Youn

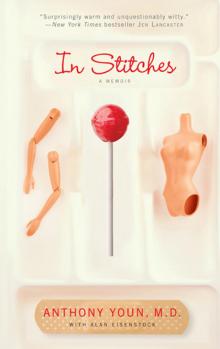

In Stitches

In Stitches Read online

IN STITCHES

Gallery Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 2011 by Anthony Youn, M.D.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Gallery Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Gallery Books hardcover edition April 2011

GALLERY BOOKS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Renato Stanisic

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Youn, Anthony.

In stitches / Anthony Youn with Alan Eisenstock.

p. cm.

1. Youn, Anthony. 2. Plastic surgeons—United States—Biography. I. Eisen-stock, Alan. II. Title.

RD27.35.Y68A3 2011

617.9'5092—dc22

[B]

2010044106

ISBN 978-1-4516-0844-1

ISBN 978-1-4516-0883-0 (ebook)

Author’s Note

This work is a memoir. I have changed names and some identifying details of many characters portrayed in this book—including all the doctors and patients—and a few individuals are composites. In some instances, the precise details or timing of events have been changed or compressed to assist with the flow of the narrative, and some comedic license has been taken. Nevertheless, I believe this book provides an accurate portrait of my journey to become the doctor (and man) that I am today. I hope you enjoy it.

For Amy, the love of my life.

Contents

Prologue: The Face in the Ceiling

I: Premed

Chapter 1: Karate Kid

Chapter 2: Jawzilla

Chapter 3: Zero for Four Years

II: First Year

Chapter 4: Little Asia

Chapter 5: Master of the Shopping Cart

Chapter 6: A Show of Hands

Chapter 7: Nerd Room

III: Second Year

Chapter 8: Flower Street

Chapter 9: No, But I Play One on TV

Chapter 10: Second-Year Crush

IV: Third Year

Chapter 11: First Do No Harm . . . Oops

Chapter 12: Role Model

Chapter 13: “Miracle of Birth Occurs for 83 Billionth Time!”

Chapter 14: If You Don’t Cut, You Suck

Chapter 15: Shrink Rap

Chapter 16: This Is Spinal Tap

Chapter 17: Mommy Dearest

V: Fourth Year

Chapter 18: Thanksgiving Story

Chapter 19: Beverly Hills Bloodsuckers

Chapter 20: Monkey Time!

Chapter 21: Match Madness

Acknowledgments

IN STITCHES

Prologue: The Face in the Ceiling

What a pair. Double D’s. Poking up at me like twin peaks. Pam Anderson, eat your heart out.

Too bad they’re attached to a fourteen-year-old boy.

I ease the black marker out of my lab coat pocket and start drawing on my first surgery patient of the day. Phil. An overweight African-American boy. Phil has severe gynecomastia—in layperson’s language, ginormous man boobs. Poor Phil. Bad enough being fourteen, awkward, and a nonathlete in a tough urban Detroit school. Now he has to deal with breasts?

Two weeks ago.

I sit in my office with Phil and Mrs. Grier, his grandmother. Phil lives with his grandma, who’s raised him since he was ten, when his mom died. He’s never known his dad. Mrs. Grier sits on a chair in front of my desk, her hands folded in her lap. She’s a large woman, nervous, well dressed in a light blue dress and matching shawl. Phil, wearing what looks like a toga, sits on a chair next to her. He stares at the floor.

“It happened fast,” Mrs. Grier says. “He shot up, his voice got deeper, he started to shave.”

She speaks in a low rumble. She looks at her grandson, tries to catch his eye. He can’t see her. He keeps his head down, eyes boring into the floor.

“Then he became quiet. Withdrawn. He would spend more and more time in his room alone, listening to music. He would walk around all day wearing his headphones. Seemed like he was trying to shut out the world.”

Mrs. Grier slowly shakes her head. “Phil’s a good student. But his grades have gone downhill. He doesn’t want to go to school. Says he’s sick. I tried to talk to him, tried to find out what was wrong. He would just say, ‘Leave me alone, Nana.’ That’s all he would say.”

Phil clears his throat. He keeps looking at the floor.

Mrs. Grier shifts in her chair. “One day I accidentally walked in on him when he was drying off after a shower. That’s when I saw . . . you know . . . them.”

Phil flinches. Mrs. Grier reaches over and touches his arm. After a moment, he swallows and says in a near whimper, “Can you help me?”

“Yes,” I say.

I say this one word with such confidence that Phil lifts his head and finds my eyes. He blinks through tears.

“Please,” he says.

THE NIGHT BEFORE Phil’s procedure.

I can’t sleep. I lean over and squint at the clock on the nightstand.

3:13 A.M.

I twist my head and look at my wife, deep asleep, her back arched slightly, her breath humming like a tiny engine. I exhale and study the ceiling.

A shaft of light blinds me like the flash from a camera. My mind hits rewind, and I’m thrown backward into a shock of memory. One by one, as if sifting through photographs, I flip through other sleepless nights, a string of them, a lifetime ago in medical school, some locked in the student lounge studying, some a function of falling into bed too tired or too worked up for sleep. Often I would find myself staring at the ceiling then, the way I am now, talking to myself, feeling lost, fumbling to find my way, wondering who I was and what I was doing. The memory hits me like a wave, and for a second, just as in medical school, I feel as if I am drowning.

My eyes flutter and I’m back in our bedroom, staring blurrily at the ceiling. I see Phil’s breasts, pendulous fleshy torpedoes that have left him and his grandmother heartsick and desperate. I know that his emotional life is at stake and I am their hope. I know also that isn’t why I can’t sleep. I blink and see Phil’s face, and then I see my own.

I was Phil—the outsider, the outcast, the deformed. I was fourteen-year-old Phil.

I grew up one of two Asian-American kids in a small town of near-wall-to-wall whiteness. In elementary and middle school, I was short, shy, and nerdy. Then I shot up in high school. I became tall, too tall, too thin. I wore thick Coke-bottle glasses, braces, a stereotypical Asian bowl-cut hairdo, and then, to my horror, watched helplessly as my jaw began to grow, unstoppable, defying all restraint and correction, expanding Pinocchio-like, protruding to an unthinkable, monstrous size. I loved comic books, collected them, obsessed over them, and as if in recognition of this, my jaw extended to a cartoon size. I was Phil. Except I grew a comic-book jaw while he grew National Geographic breasts. Like Phil, I only wanted to look and feel normal. I just wanted to fit in.

It hits me then.

My calling—my fate—was written that summer between

high school and college, the Summer of the Jaw. My own makeover foreshadowed my life’s work. Reconstructing my jaw showed me how changing your appearance can profoundly affect your life. Now, years later, I am devoted to making over others—helping them, beautifying them, changing them. I have discovered that plastic surgery goes beyond how others see you; it changes how you see yourself. On occasion, I have performed procedures that have saved lives. I believe that I will save Phil.

My mind sifts through my days in medical school, and in a kind of hallucinogenic blaze, I conjure up every triumph, every flub, every angst-filled moment. I remember each pulse-pounding second of the first two years of nonstop studying and test-taking, interrupted by intermittent bouts of off-the-hook partying. I see myself in years three and four, wearing my short white coat, wandering through hospital corridors trying to overcome my fear that someone—an administrator, a nurse, or God forbid, a patient—would confuse me for a doctor and ask for medical attention. I teetered a hair’s width away from those moments that might mean life and death, facing the deepest truth in the pit of my stomach: that I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. And neither did any of my medical-school classmates, those doctors in training who stumbled around me.

But things changed. Thanks to my small circle of close friends, my focus, work ethic, and drive to succeed, I slowly grew up. I entered medical school a shy, skinny, awkward nerd with no confidence, no game, and no clue. I came out, four years later, a man.

A smile creeps across my face. My eyelids quiver. I catch a last glimpse of the face of my younger self in the ceiling as it shimmies and pulls away. Sleep comes at last.

Phil’s surgery goes well. Ninety minutes, no complications. I lop off his breasts with a scalpel, slice off the nipples, then suture them back onto his now flat chest. I nod at his new areolas. They have decreased in diameter from the size of pie plates to quarters. I leave Phil stitched up and covered with gauze, a normal-looking high school freshman. Good news, Phil. You will not break new ground and become the first male waiter at Hooters.

I ONCE SAW an episode of Grey’s Anatomy in which a character suggested that she—and every doctor—experienced an “aha moment” when she realized she had become a doctor.

That never happened to me. I experienced an accumulation of many moments. Some walloped me, left me reeling. Others flickered and rolled past like a shadow. They involved teachers, classmates, roommates, friends, family, actors playing patients, nurses, the family of patients, and patients themselves, patients who touched me and who troubled me, patients whose courage changed my life and who taught me how to live as they faced death, and of course, doctors—doctors who were kind, doctors who were clueless, doctors who were burned out, doctors who inspired me and doctors whom I aspired to be, doctors who sought my opinion and doctors who shut me down.

Thinking about all these people and moments, I see no pattern. Each moment feels singular and powerful. They stunned me, enveloped me, awed me, but more often flew right by me unnoticed until days, weeks, months, years later. Until now.

This is my Book of Moments.

I Premed

1

Karate Kid

November 2, 1972.

Detroit.

I am two days old.

My father stops the car outside of our apartment. My mother waits for the engine to cut out and for my father to haul up the emergency brake. She leans into the back, lifts me out of my car seat, swaddles me inside her coat, and carries me to their bedroom, where she lowers me gently into my bassinet at the foot of their bed. My dad trails, wearing a suit, hands clasped in front of him as if in prayer. He looks down at me, and his heart fills up. He fights a grin, keeps his face tight as leather. He would never allow his feelings to spill over and make an unscheduled appearance. That’s not his way. Still, he can’t keep his eyes off of me.

“Anthony,” my mother whispers. “Good name. Strong.”

My father nods. “A doctor. Surgeon. Vascular. Big money.”

My mother blows out a sigh, tips her head onto my father’s shoulder. “Don’t rush him. Wait until he’s at least a week old.”

“You’re right.” He smiles, curls an arm around my mother’s shoulders. “Transplant surgery. That the big money. You not believe what they get. One surgery. Ten thousand dollah. For one hour. Early retirement. Mercedes-Benz. Condo in Florida—”

She lifts her head, knocks him back with a stare.

My father blinks at her. A prisoner of her eyes. “What?”

“Why don’t you tell him he has to marry a nice Korean girl, too?”

“No. Come on. He’s two days old.”

My mother rolls her eyes, nudges her head back onto my father’s padded pin-striped shoulder.

“That he already knows,” my father says.

GREENVILLE, MICHIGAN. POPULATION 7,945.

I am six years old.

I’m learning English. I’ve picked up most of it from watching Sesame Street and spending my days at my friend Chris’s house. My father doesn’t know. Or if he knows, he doesn’t let on. I’m sure he wants me to learn English, even though he and my mom are heavily into their Korean roots. We do live in America, and I am going to be a doctor, so it would be helpful if I knew English, even though I’d rather not be a doctor. I’d rather be a superhero or own a toy store.

My father casts a huge shadow in our house, in my life, although when I think about it, I see him only once a day for about an hour. He works long hours, often leaves when I’m asleep. He always comes home for dinner. When we hear his car grind into the driveway, my older brother, Mike, and I stop whatever we’re doing and race to the front door to greet him. Sometimes I get lost playing with my toys or flipping through a book, and I zone out. Takes me a minute to come back to earth, to regroup. But the instant that front door opens, I snap out of my trance, scramble to my feet, and race Mike to the door.

Something happens in the house when my father walks in. The atmosphere shifts. The air feels heavier. My father changes the energy in the room, too. Slows it down. Makes you more careful. And I know this. You do not want to get him mad. I’m never sure what will upset him. He’s like the weather. Cloudy with a chance of rain and occasional thunderstorm.

“Good evening,” my father says in Korean to my brother and me at the door. Sometimes I feel less like his son and more like his employee.

“Good evening, Father.” We answer in Korean, and then we bow. He doesn’t give us a full bow back. He bends slightly. He’s the authority. That’s all he has to do.

“How was your day?” I ask him.

“Fine.”

Mike, a year and a half older, grunts, avoids eye contact. I can feel my father staring at him.

“Anything interesting happen?” I ask, trying to deflect, trying to avoid any imminent storm on the horizon.

Eyes first on Mike, then sweeping back over me like a prison searchlight, my father says, his voice weary, “Rake the leaves” or “Sweep out the garage.”

My father doesn’t believe that his sons should be idle for a minute. When you finish a job, there is always more work to be done. Banished to the backyard or en route to the garage, I turn back for a moment and catch my father smiling at my mother, a knowing, familiar smile, the closest they ever come to intimacy in front of us. He’ll then make his way into the family room, plop down in his La-Z-Boy recliner, wriggle out of his shoes, put his feet up, and open the evening paper. Soon my mother will arrive with a drink, orange juice or tea, then return to the kitchen and finish preparing dinner. My father will flip on the TV, lay the newspaper on his lap, and stare at the evening news.

Outside, my brother and I alternate stretches of working hard with slacking off. The leader, he’ll lean on his rake or broom, make cracks at me, or fool around and attack me, turning his rake or broom into a weapon. But no way will we go inside for dinner with the leaves not raked or the garage not swept. I’m not sure what my father will do, but I know that he’ll punish us, and

I’d rather not find out how. Even at this young age, I’ve learned certain survival skills. Top of the list, I avoid confrontation at all costs.

My parents, both Korean émigrés, try to retain some of their native traditions. My mother has decorated our walls with traditional Korean art. She reads me popular Korean children’s stories, sings Korean children’s songs, and recites Korean folk tales. And she cooks traditional Korean food. Seafood, mostly. Scary seafood. I walk casually into the kitchen and find myself facing the dead eyes of a two-foot-long fish flopped across the kitchen table, which, steaming in its own succulent juices, we will pick apart later with chopsticks. More often my mother will serve us tureens of sizzling squid and octopus soup, tentacles and snouts bobbing, attached to, I swear, half-alive mini–sea monsters, devil fish that we have to batter and subdue before we choke down the slimy morsels with mouthfuls of sticky rice. Recently, on the sly, Chris and his family have introduced me to McDonald’s, Pizza Hut, and KFC, and I have fallen hard, beginning a hot and heavy love affair with American fast food.

When dinner is ready, my mother calls to us or rings the dinner bell. Mike and I finish raking or sweeping and dart inside. I wash my hands, then head into the family room and tell my father in Korean that it is time for dinner. At dinner, we speak little and only in Korean.

Tucking me in at night, my mother brings the covers up to my chin. I turn to her and whisper, “Why do we always have to work when Daddy comes home?”

“Your father believes in hard work. That’s how he was raised.”

“On the farm.”

“Yes. On the farm. He believes you have to get your hands dirty.”

“He never does.”

My mother’s eyes bore into mine.

“Well, he doesn’t,” I say. “Mike and I do all the work. And you.”

My mother’s lip quivers. I can’t tell if she’s about to yell or laugh.

“He works very hard. At night when you’re sleeping, he gets calls, all the time, to deliver babies. He has to go out in the middle of the night. He’s the only baby doctor in town. That’s why he’s so tired all the time. He works all day and all night.”

In Stitches

In Stitches